Aridification diminishes the ability for species to thrive if they cannot move to better conditions. Migratory birds are often able to move to areas with better habitat conditions. Loss of irrigated rice fields in Texas contributed to significant declines in wintering waterfowl along the Gulf Coast. Playa lakes in the High Plains serve as important habitat for migrating waterfowl, but these can disappear during drought.

Climate change may be one factor in plant community changes. In turn, these changes affect fish and wildlife. In the Southern Great Plains region, winters are getting warmer and spring is arriving earlier. Along the Texas coast, black mangroves are expanding northward along the coast, and red mangroves, formerly not found in Texas, are now appearing there.

Aquatic Ecosystems

Higher water temperatures in lakes, wetlands, rivers, and estuaries can result in lower dissolved oxygen, leading to more fish kills. Impacts to reservoirs include fluctuating lake levels, loss of habitat, loss of recreational access, increase in harmful algal blooms, and disconnectedness from upstream and downstream riverine habitats. Researchers have seen local declines in fish populations in rivers due to lack of water or water confined to increasingly narrow pools. Aridification can also have negative impacts on freshwater mussel populations.

Coastal Areas, Bays, and Estuaries

The Texas coast, with 6.5 million people contributing over $37 billion to the region's economy, benefits from bays and estuaries that serve as storm barriers to protect coastal infrastructure. The area also benefits from ecosystem services such as fishing, ecotourism, and the ocean economy. The region’s coastal ecosystems provide protection not only for people, but also for 25% of the Nation's refining capacity, including four crucial ports, much of the strategic petroleum reserves, and strategic military deployment and distribution installations.

Rising seas are impacting beaches along the Texas coast where the average rate of beach erosion is almost 10 feet per year. Sea level rise also means more frequent and longer-lasting flooding of marshes; if they are permanently flooded, protective marshes may become open water. Higher tides and storm surges cause inundation of freshwater areas and beach erosion, leading to a potential decrease or loss of barrier islands and coastal habitats, including nesting habitats and submerged habitat such as seagrass beds. A significant percentage of fishery species in the Gulf of Mexico are dependent upon estuaries for some portion of their life cycle.

Bay waters along the Texas coast have been warming for at least 35 years, more so from warmer winters than warmer summers. The increase in water temperature directly affects water quality, increasing the potential for low levels of dissolved oxygen, or hypoxia. Hypoxic events and harmful algal blooms have caused fish kills, resulting in lower productivity and diversity of estuarine ecosystems. Rivers flowing into coastal estuaries bring important nutrients and sediments that help maintain productive estuarine ecosystems. Reduced inflows of surface and groundwater from the Southern Great Plains have led to dramatic changes of the aquatic and wetland communities in inland locations as well as the coastal ecosystem. Changes in salinity, nutrients, and sediment have impacted oysters and other sensitive estuarine species. In addition, harmful algal blooms have become more frequent, more intense, and more widespread.

Reduced freshwater inflows during 2011 led to record high salinities in Texas estuaries that contributed to a coast-wide “red tide” harmful algal bloom event. Red tides, a type of harmful algal bloom, most commonly occur during drought years, as the organism that causes red tide does not tolerate low salinity. Red tide blooms cause fish kills and contaminate oysters. In addition, oysters and other shellfish can accumulate red tide toxins in their tissues. People who eat oysters or other shellfish containing red tide toxins become seriously ill with neurotoxic shellfish poisoning. Once a red tide appears to be over, toxins can remain in the oysters for weeks to months. The 2011 bloom started in September and lasted into 2012. Fish mortality was abnormally high and the commercial oyster season was closed.

Human Health

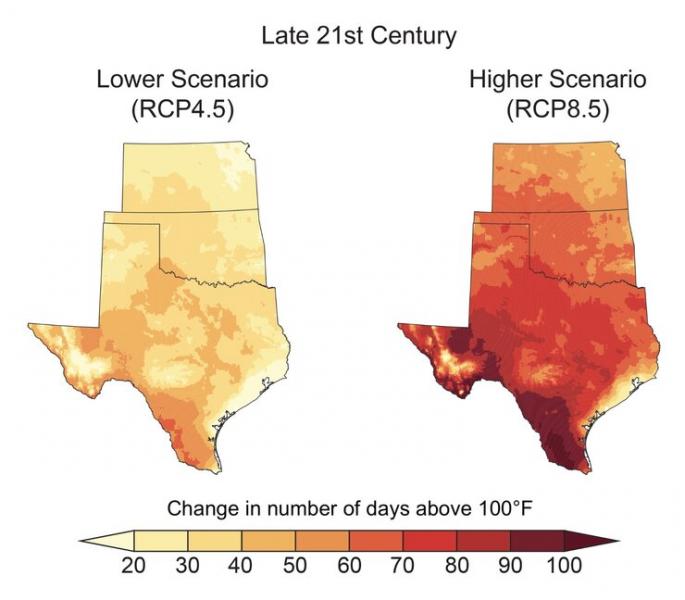

Extreme heat can have significant impacts on healthy individuals in the Southern Great Plains and it acts as a threat multiplier to the medically vulnerable. For instance, heat stress is strongly correlated with complications of lung disease such as asthma and emphysema. Additionally, increases in summer temperature are correlated with increases in the death rate for older individuals with chronic conditions. During the hot summer of 2011, the average temperature in Texas from June to August broke all previous single-month records. Studies also revealed a 3.6% increase in emergency room visits and a 0.6% increase in deaths. Within the Southern Great Plains, changes in extreme temperatures are projected to result in an additional 1,300 deaths per year by the end of the century if emissions of heat-trapping gases continue increasing. If emissions decrease substantially, more than half of these additional deaths could be avoided.

Populations of mosquitoes, ticks, rodents, and fleas that transmit a variety of human diseases may increase in the Southern Great Plains with rising temperatures and precipitation. Historically, extreme low temperatures in winter controlled insect populations. Now, higher temperatures let insects such as mosquitoes—and the diseases they carry—thrive longer and reproduce more successfully at higher latitudes and altitudes.

Drought conditions reduce the number of sources and overall quantity of water for both humans and animals. As they share a reduced supply, germ transmission and outbreaks of infectious disease between humans and animals become more likely. Several waterborne diseases have been linked to drought. Skin infections, such as scabies and impetigo, and eye infections, including conjunctivitis, are also correlated with drought.Droughts, floods, and higher temperatures give invasive species a chance to proliferate, and these can harm crops and livestock. Additionally, the nutritional value of some crops are reduced as carbon dioxide levels increase.

Extreme temperatures pose serious health risks to outdoor agricultural workers. By the end of the century, if emissions of heat-trapping gases continue increasing, temperature extremes are projected to result in the loss of about two billion hours of labor across the nation. And the Southern Great Plains region is projected to experience higher-than-average impacts. Many states are developing plans and enhancing healthcare infrastructure to monitor climate-sensitive infectious diseases. Incorporating short-term to seasonal forecasts into public health activities can also help protect people as temperatures increase. Although there is some momentum to adopt adaptation strategies to improve health outcomes, large-scale efforts are still lacking and regional planners may learn from activities ongoing outside the region.

Indigenous Peoples

Water resource constraints, extreme weather events, higher temperature, and other public health issues conspire to increase the climate vulnerabilities of Tribal and Indigenous communities in the Southern Great Plains. Efforts to build community resilience can be hindered by existing limitations, yet traditional knowledge and intertribal organizations offer unique opportunities to adapt to the potential challenges of climate change.

While Tribes and Indigenous peoples across the Southern Great Plains generally experience the same climate change impacts as the rest of the Nation, these sovereign nations face unique challenges and opportunities in their response to climate change impacts. The biggest challenges to tribes and Indigenous peoples of the Southern Great Plains are those that threaten their ability to procure food, water, shelter, and preserve ancient cultural activities. Given the strong relationship between environment and culture, climate-induced changes to the seasons, landscapes, and ecosystems pose an existential threat to cultural traditions and community resilience. The impacts of excessive heat, drought, and the disappearance of native species are already disrupting some cultural practices.

The region’s tribes and Indigenous peoples vary greatly in size. Some of the regions’ larger and wealthier tribal nations are working to develop and shape their own climate adaptation strategies. Conversely, some of the smaller nations, due to a relative lack of social and physical infrastructure, often struggle to exercise their sovereignty to respond to climate change. Consequently, the smaller tribes depend largely on the services, grant programs, and technology transfer capabilities of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and other Federal entities to support their climate adaptation efforts.

Lack of physical infrastructure, tied directly to limited economic resources and power, poses a substantial obstacle to climate change adaptation for the tribes of the Southern Great Plains. While cities and other governmental jurisdictions make plans to build resilient physical infrastructure by using bonds, public–private partnerships, and taxes and tax instruments, only a handful of tribal nations have the ability to use these tools for climate adaptation. Most tribes and Indigenous peoples remain dependent on underfunded federal programs and grants for building and construction activities to improve the resilience of their infrastructure in the face of climate change threats.

In response to their changing environment, some Tribes in the region are implementing adaptation measures and emissions reduction actions. Some of the larger and wealthier tribes have modeled construction and design of homes and large commercial building best practices on “green” or resilient net-zero carbon footprint designs. Increasing activity in community gardens, food recovery, recycling, water conservation, land-use planning, and investment in climate-resilient community design all signal opportunities for tribal nations to leapfrog significant obstacles other city, county, and state governments face when dealing with the costs of existing physical infrastructure that often make climate change adaptation difficult and incremental.